Some reflections on recent developments in the Lesson Study literature: what should LS take from these studies for their pupils’ learning, their practice and their own professional learning?

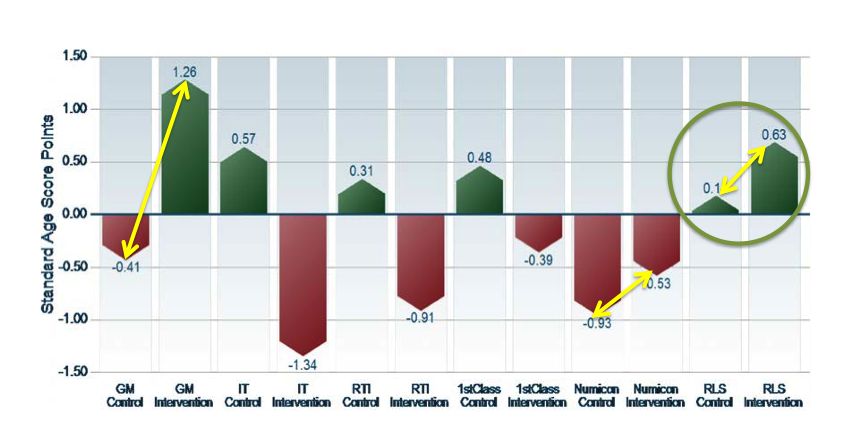

I was pleasantly surprised last year to find that a randomised study carried out by the DfE comparing the effectiveness of a number of pedagogical and curricular interventions in closing achievement gaps showed that Lesson Study (LS) had the second overall highest impact on raw test results and had a modest effect size. (See Fig. 1 below labeled RLS [1])

Figure 1. SAS score points reduction in attainment gaps. Closing the gap: test and learning, (DfE 2016)

[1] When I first introduced LS I called it ‘Research Lesson Study’ or RLS (Dudley, 2003, 2005) but dropped the word ‘research’ in 2008 when we introduced LS into the National Strategies on advice that it might put people off).

I was surprised because Lesson Study is not a pedagogical nor a curricular intervention. LS is an andragogical intervention designed to enhance teacher (adult) learning. Obviously one would expect that teacher professional learning should ultimately impact on the progress of the children they are teaching – though perhaps not instantaneously. My hopes for this trial had therefore not been high. I did not think that measuring a teacher learning approach would reveal anything much by way of immediate impact – especially when it was up against a selection of pedagogical/curricular interventions that were operating directly on pupil learning.

It might have been more informative to look at the curricular/pedagogical interventions with or without LS. However, if Numicon or GM (which both had positive gap closing scores) had been evaluated with and without LS and then the same thing had been done with two of the other interventions above that had negative comparative effects on closing the gap, I am still not sure what the results have told you about LS.

David Weston’s blog for the Teacher Development Trust of 10 November makes some similar points very well in relation to findings of another more recent randomised control trial (RCT) published by the Education endowment Fund http://tdtrust.org/author/david-weston . David points out that in this trial:

- the pedagogical interventions used with the children were also called ‘Lesson Study’ so ‘apples and pears’ were being unhelpfully combined;

- a lot of schools that were in the ‘control’ group and thus had been asked to go away and not do Lesson Study for two years (despite applying to join a LS project!) had in fact gone ahead and used it during the trial period (which the evaluators conceded could explain the lack of a difference between the control group and the treatment group).

There was also a gap of 12-18 months between finishing the lesson studies and the pupils in the classes in which they were carried out taking their KS2 tests on which the findings were based. David also cites studies such as that by `Lewis and Perry (2016) where using a lesson study approach with a structured teacher subject knowledge toolkit for teaching fractions produced a .49 effect size. This improved the lowest attainers to levels close to the previous average and the average to the levels of the previous highest. The study was one of only two of 643 cleared by the US research authorities for design and impact quality. That said, I am pleased that a body like the EEF is investing in research in teacher learning and CPD – an under researched area.

I am with David Weston completely on being disappointed – but not surprised at the outcomes of the EEF trial for the reasons above. The literature on lesson study is still immature but broadly positive and there is a growing body of research in progress that will help us understand things more fully. What we do not know from the EEF study is whether these results were uniform across all the schools or whether there were some schools or classrooms where there was evidence of impact and others to the contrary, and what we know about the way that the components of pedagogical intervention and teacher learning about that through lesson study looked like.

I also agree with huntingdon.researchschool.org.uk which on 21 November questioned whether teacher observation alone can improve teaching – when we know that teaching is a complex process and that much of the teacher practice knowledge this is designed to improve is tacit in nature. (If watching things alone improved practice then we would by now be a nation of ballroom dancing virtuosos with cordon bleu baking skills to match!)

What I disagree with here though is the assumption behind this that LS is a ‘teacher observation approach’ to improving teaching. It is not.

In truth LS is a highly deliberate, collaborative ‘learner observation approach’ aimed at helping teachers to improve pupil learning. Before any observation occurs, LS involves teachers in collaboratively assessing, researching and planning pupil learning in jointly constructed classroom activities that should of course draw on (i) evidence based approaches – but also (2) on their abilities to tailor those approaches to the needs and idiosyncrasies of the pupils in that specific class. And when observation does occur in the research lessons it is focused on the pupils’ learning.

Figure 2 below reproduces Catherine Lewis’s analysis of the forms of analysis and learning that teachers engage in at each stage of the LS process.

In fact there is growing evidence that lesson study can create the conditions where some of those untapped reserves of tacit practice knowledge are made explicit to the point where they can inform future practice (Dudley, 2013; Warwick et al 2016). One of the main points of LS is that it allows teachers to develop their professional practice together – even in areas of perceived vulnerability and weakness – and that this means they can engage in disclosing and working on aspects of their practice (and subject knowledge and pupil knowledge) in which they are less confident as teachers. This newly developed practice knowledge is deepened when they coach others in its use or share the new knowledge with colleagues in other ways.

Gaps in expert knowledge of subject or curriculum

All this also goes back to my initial and overall concern with the claims being made at the outset. LS is a process for teacher learning and for developing practice-knowledge as a result of improving teachers’ understanding of their pupils as learners, or of the subject they are teaching. Or more usually – they develop a combination of both. They gain a better understanding of how to teach that subject knowledge in the light of improved understanding (created by the lesson study) of how their pupils were learning or failing to learn the subject, and…. what could be done next time to improve it.

In carrying out the Closing the Gap study cited at the start of this piece, CUREE decided to focus on disengaged pupils whose teachers thought of them as ‘Really Here In Name Only.’ The research lessons teachers designed aimed to help them to understand the nature of these pupils’ disengagement by treating them as ‘case pupils’ who were carefully studied in the research lessons. This helped teachers to diagnostically assess them and to devise improvements – affective as well as cognitive – to support their learning in the next research lesson. The materials that CUREE provided to teachers also guided them in key aspects of subject and ‘pedagogical content knowledge’ needed for the learning– something Catherine Lewis has also done in similar trials with ‘content knowledge packages’ in the US.

In fact when we experimented with LS in the National Strategies (2008 -9), we also included subject experts in the mix. We worked with ‘coasting schools’ who were allocated ‘leading teacher’ specialist coaches. They worked with year six teachers on either English or mathematics. Half the leading teachers (around 400) were trained to use a LS approach. The other half used traditional ‘leading teacher’ strategies of demonstration and modeling. Hadfield et. al. in their review of this work (DfE 2011) showed that the improvement in KS2 test scores made by schools with the LS approach was around double that of those using the traditional leading teacher approach which themselves had improved ahead of the national rate.

So I also agree with @PhilippaCcuree who in comments earlier this month also related the responses to the EEF report, recently stressed that when a teacher subject knowledge gap is causing a pupil learning problem, the inclusion of a subject expert in a Lesson Study group set up to solve the problem is a must. In fairness, most schools using LS get this and use their subject leaders as LS group members accordingly. The same is true at organisational level. So if you want to improve learning in a subject aspect in which no one in the school – not even the subject lead – has expertise, it makes sense to bring in an expert in the knowledge gap area to advise or even better to join the lesson study group: a ‘knowledgeable other’ in Japan.

But I want to return again briefly to the role of lesson study in helping us understand our pupils and to become experts in their learning which at the heart of Lesson Study’s purpose and so often missed as we can see here.

Gaps in teacher knowledge of ‘these’ pupils

The unique strengths of Lesson Study are not in ‘magicing’ subject or other pedagogical/curricular knowledge into the heads of teachers. They are in helping teachers to see their learners with fresh eyes and to better understand: what the pupils know, how to connect that to the new knowledge in hand and how to diagnose what might be creating barriers to the pupils in doing this (Warwick, et. al. (2017).

The deliberate LS process of jointly predicting what a case pupil’s learning will be when planning, and then checking what is actually learned through close, joint observation in the research lessons, is one of the ways that lesson study reveals previously unseen aspects of the learning of case pupils and others in the class. Most LS groups discover ‘unknowns’ about at least one pupil in the class almost every research lesson. And you can respond to that discovery the very next time you teach them.

LS groups also form such close, reciprocal relationships through their shared endeavour and focus, that they are able to draw upon and utilize their members’ vital but mercurial tacit knowledge of practice which in most other CPD contexts is unknowable and unreachable (Dudley, 2013).

In dealing with teacher subject knowledge gaps, we are usually dealing with known unknowns. But when it comes to what we don’t know about our pupils-as-learners, we are often dealing with unknown unknowns. It is unknown unknowns that Lesson Study is particularly adept at making visible.

So if the gap in the expert knowledge in school concerns pupils with particular needs, the same may well apply. I first used a lesson study approach 30 years ago with teachers who were encountering children learning EAL for the first time. Even those with the most expert subject knowledge did not know the pedagogical approaches that best support beginners in English or those pupils whose basic interpersonal communicative skills in English were good but who still needed to develop more complex and hidden cognitive and academic language proficiency – which often has subject specific genres.

In such cases inviting experts in specific aspects of learning disability or difficulty into the school to join or advise a lesson study group is just as important as inviting experts in a subject or intervention. Lesson study will then help unlock and transfer that knowledge into your teacher population enabling further distribution of the knowledge and practice through involvement your new internal experts in in-school lesson studies.

Analysing the distribution and strength of such expertise in a school is seldom cut and dried, and will require judgment calls. There are of course other issues to consider in assembling the most effective LS group for any particular situation as well – experience, personalities, availability and capacity. Figure 2 below suggests a rubric to help leaders weigh the options in relation to the subject expertise v pupil expertise question.

In summary

‘Lesson Study organises the known components of effective teacher professional learning, highly effectively and reflectively and reflexively.’ (Xu and Pedder, 2015).

LS is in use now not only in schools but in early years settings, FE colleges and universities; by subject experts and specialists in learning difficulties and disabilities. Clinical psychologists now use Lesson Study to explore how brain traumas have affected children’s learning and how best to respond pedagogically.

Lesson Study will not help approaches that don’t work work! Nor, in my view, should LS be seen as an ‘observation’ treatment to be wheeled out occasionally for use with one off interventions. Research Lesson study is a deliberate process of what Akihiko Takahashi terms ‘collaborative lesson research’. More studies will unfold and these will enrich what we know and help develop collaborative classroom teacher learning approaches like research lesson study, collaborative lesson research, learning study – all variants on the lesson study theme.

But plumbed into the rhythms and processes of your school, LS will help you both to optimise what is working and to introduce, adapt and embed practices proven elsewhere. LS is a professionally healthy and fulfilling way of continually sharpening teaching, practice knowledge and learning community in response to the evolving demands of learning itself and the ever changing needs of learners – whether they are children or professionals.

Pete Dudley

November 2017

References

NCTL Mind the gap: test and learn. Dudley, P. (2013) Teacher learning in Lesson Study: What interaction-level discourse analysis revealed about how teachers utilised imagination, tacit knowledge of teaching and fresh evidence of pupils learning, to develop practice knowledge and so enhance their pupils’ learning, Teaching and Teacher Education, 34. (2013) 107-121.

Hadfield, M., Jopling, M., Emira, M. (2011) Evaluation of the National Strategies Primary Leading Teachers Programme, London, Department for Education.

Xu, H., and Pedder, D. (2015) Lesson Study: an international review of the research, in Dudley, P (Ed.) Lesson Study: Professional Learning for our time, London, Routledge, pp. 24-47

Lewis, C. and Perry, R. (2016) Lesson Study to Scale Up Research-Based Knowledge: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Fractions Learning Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 2017, Vol. 48, No. 3, 261–299

Follow lessonstudyuk

Pingback: Interesting Reads: Lesson Study For Professional Learning | joannemilesconsulting